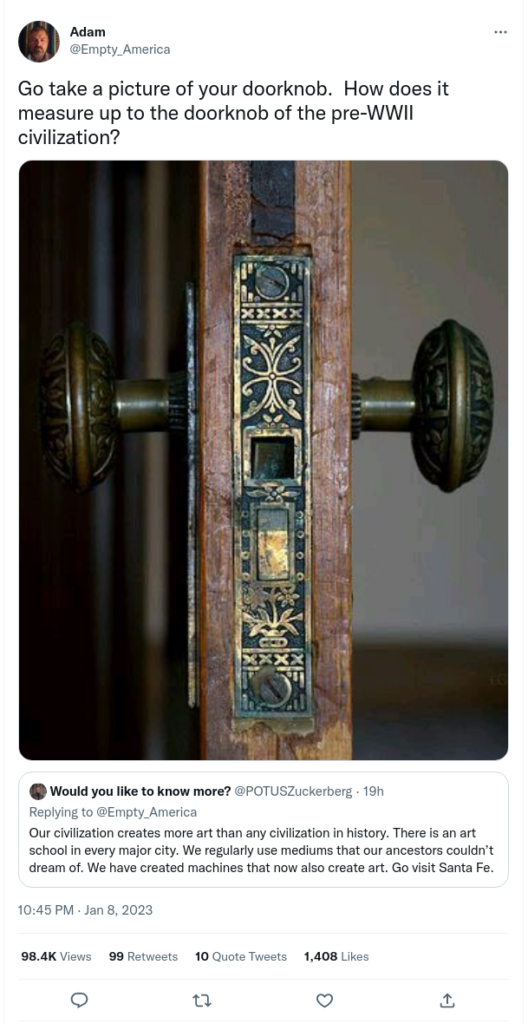

I get the impression that things are much less decorated than they used to be. This has been explained to me as because of the increased cost of labor, which has some issues but to me wins out over other explanations. Some other explanations I’ve heard are that people are overstimulated in life and don’t buy decorative stuff so they have a place to recover, that plainness and lack of decoration is the new class signalling, and that a different civilization is responsible for all the nice stuff we see historically but don’t see built any more. These may later explanations may be more correct but they are unverifyable, while the first points to a specific effect that is definitely true. An issue with the first explanation is that the ultimate cost of e.g. nice decals, impressions onto stamped metal, has also been made lower due to technology, but maybe less so than the thing itself. Regardless, I appreciate nice looking things and soulful things and want to live in a world with more of them.

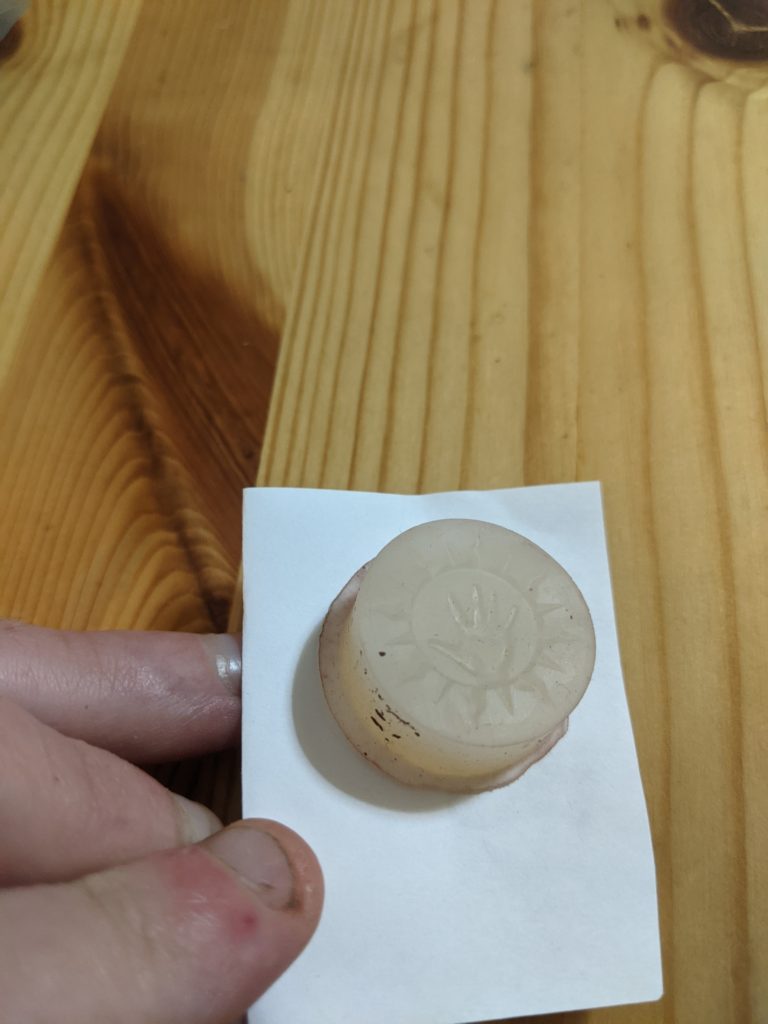

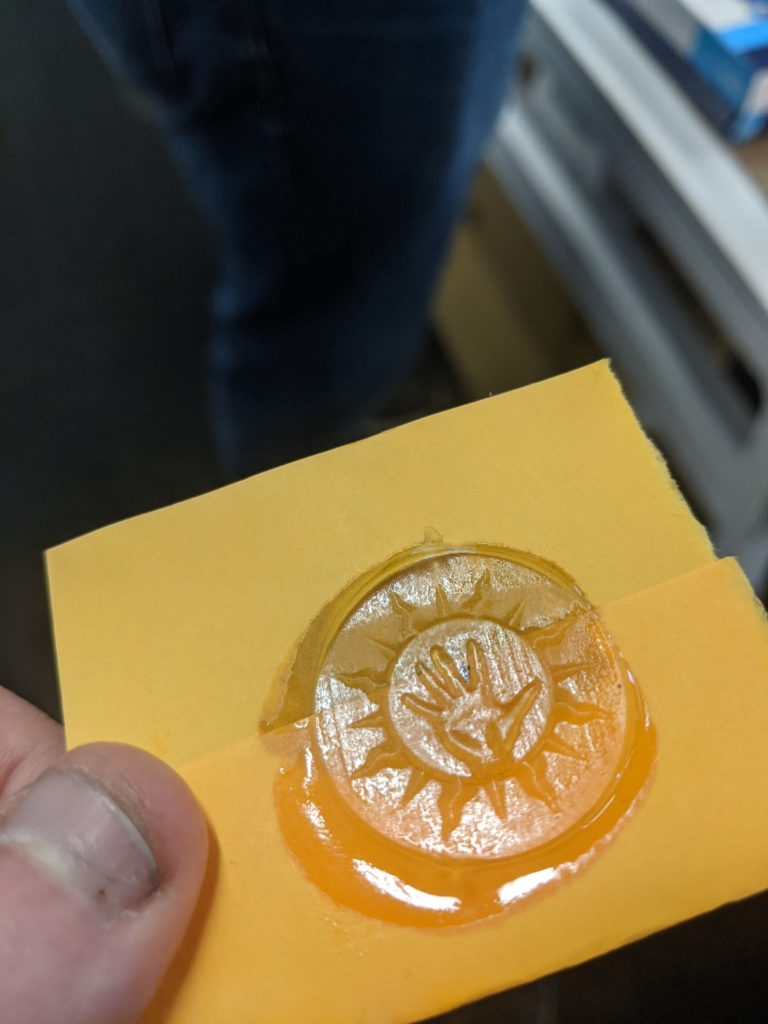

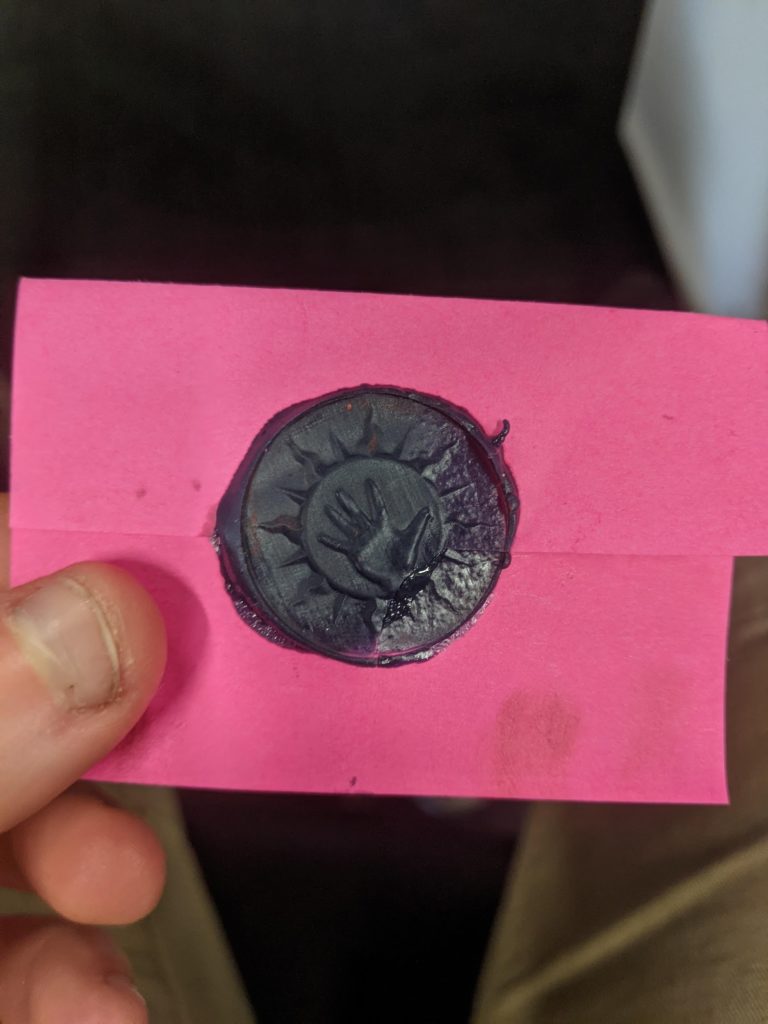

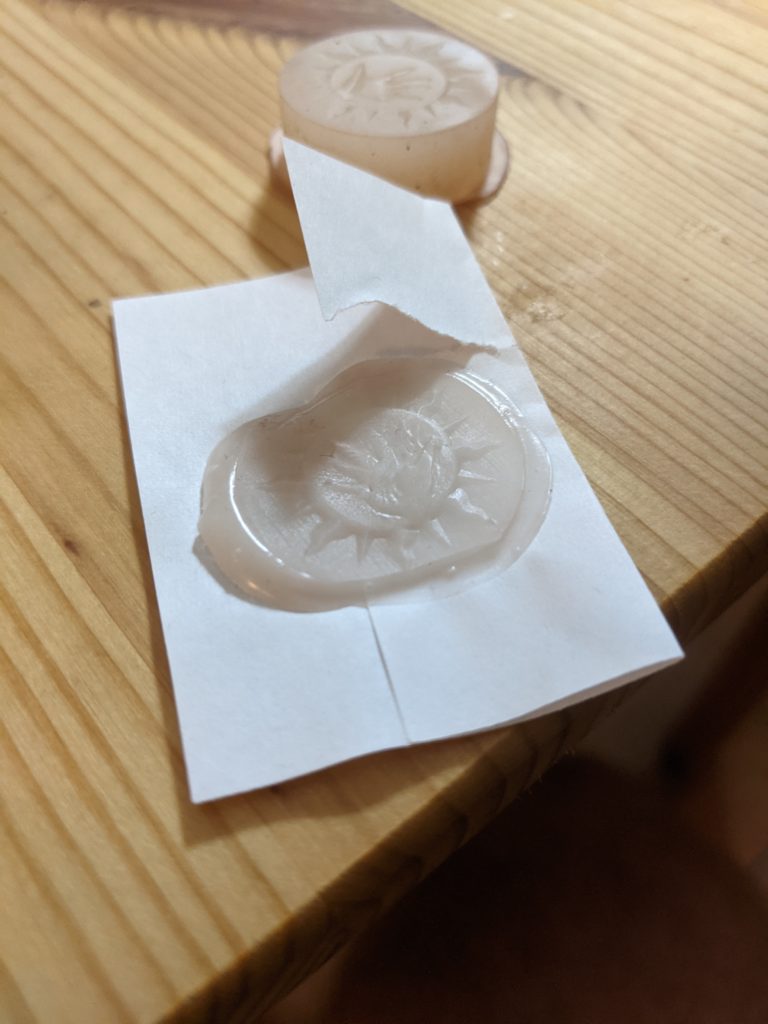

Costs can be split into manufacturing costs and design costs. Something neat to me about additive manufacturing is that for a lot of methods, decorations are free, or atleast very low cost. The decorations can also be different for each object produced. For example, Desktop Metal has a binderjet printer that prints wood (sawdust+binder) and dyes the material to resemble different types of wood (Forust). Because it’s a binderjet printer, small model changes for e.g. fake engravings don’t affect print time or cost, and because the material is already volumetrially dyed having custom colorations and patterns and images should also come free. This is the best example, but all binderjet printers and resin LCD printers should have basically free 3D decorations, and many 3D printer methods that allow color have the same print time cost regardless of the color used. Of course, all these methods rely on 3D printing actually being a competitive way to design a mass produced product, but in my impression that’s already what a lot of 3D printing companies are betting on anyway. There are also many cases where literally the same object is sold from different places with several fold differences in cost so I think it’s very possible that most people would be willing to pay a small premium for custom items.

This leaves design costs. While I think there’s some human intervention required, there’s a lot of neat generative deep learning work that could be used to take the load off of human artists. For example, given a model of an object to print, a human probably needs to label visible surfaces vs. critical surfaces (surfaces which must remain unchanged for function). At the lowest end of engineering difficulty, aesthetic patterns or simple random textures/tilings can be applied. There are manufacturing methods which produce results like this already, where every customer gets a slightly different object in a nice way. At higher levels of engineering difficulty, generative deep learning models could produce stylized and themed decorations according to the desires of the consumer. I’m still thinking this side of everything through, so I’m collecting examples of technologies and art. While I have some experience making and training generator deep learning models, it’s not something where I’ve ever been happy with the result.